| Key | Value |

|---|---|

| Author | Johann-Mattis List |

| Date | 2025-07-23 |

| Version | 0.2 |

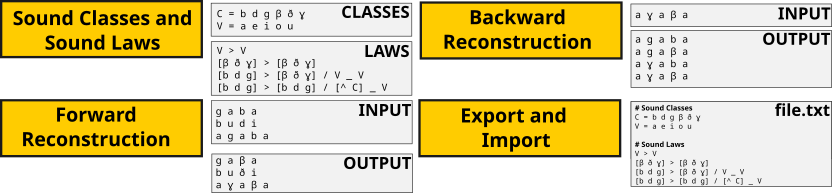

MISOl consists of four major components accessible in four different tabs of the web interface. The first component defines sound classes and sound laws. The former allow to group sounds into arbitrary units, and the latter allow to define how sounds in an ancestral language change into sounds in a descendant language in a certain context. The second component allows to convert words in the ancestral language into words in the descendant language (also known as “forward reconstruction”), and the third component allows to guess from which words in the ancestral language a given word in the target language has evolved. The fourth component allows to import and export data in text form, enabling users to store their analyses, parse the data with additional software tools, or to compare different approaches to solve the same problem in phonological reconstruction. The components are summarized in Figure 1.

The table of sound classes defines sounds in a very simple way, by assigning one or more sounds or sound classes to a certain sound class label on each line. Sound classes are read in from the first to the last line and definitions are stored at the time a line is parsed. As a result, sound class assignments can be combined, and an existing sound class can be assigned to another class.

The assignment of one or more sounds or sound classes to a given sound class is represented in the form:

name = sound1 sound2 sound3The name of a sound class must be alphanumeric, similar

to typical Python variables, and should not start with a number. The

=-sign must have a space to the left and to the right. All

sounds (or sound groups referenced by invoking an existing sound class

name) must be separated by a space.

Thus, the following examples for sound class definitions are all wrong:

name=sound1 sound2 sound3

name =sound1 sound2 sound3

name= sound1 sound2 sound3

1name = sound1 sound2 sound3Internally, a sound class is an ordered list of sounds. By assigning sounds to a sound class, the sounds are made available to the MISOL system to act as source and target of sound change processes and to be referenced in sound laws. In addition to referencing groups of sounds with the help of sound class variables, all individual (“terminal”) sounds are also represented in as sound classes. The difference is that these classes have the same label as the sound iself and that they contain only one element (the sound they refer to).

Furthermore, each final symbol that is identified as a sound (and not a sound class name) by the MISOL system is also assigned to its own class with one single manner. Thus, the following line will define as many as 5 internal sound classes, of which four have one single member, and the first targets the four only sounds in the system.

my_class = a b c dThus, internally, this will result in the following key-value representation:

{

"my_class": ["a", "b", "c", "d"],

"a": ["a"],

"b": ["b"],

"c": ["c"],

"d": ["d"]

}When parsing sound laws, MISOL automatically checks for sounds that have not been referenced in the sound class table and adds them as individual sounds to the table of sound classes. As a result, you do not need to define sound classes in order to define sound laws.

In order to check which sound classes have been defined in MISOL, click on the SHOW CLASSES AND LAWS button, after having inserted your sound class definitions and your sound laws in the Classes and Laws tab. A table will open and present you all sound classes that have been defined, including both those classes that you defined actively, as well as those classes that were inferred automatically from the sound laws you defined.

When you check the sound classes in MISOL, you will see that the list

of classes shows three sound classes in the beginning, which are

provided independently of what you have defined or not. These reserved

classes, are the symbols ^, $, and

-. ^ refers to the beginning of a sequence and

can be used in the context string of a sound law. The same holds for

$ referring to the end of a sequence. - refers

to a specific sound law in which an element is lost (rather than being

replaced by something). It can also be used as a source sound (in the

case of epenthesis, which must be actively modeled) or as a target sound

in a sound law. Other than for this specific purpose, the symbols should

not be used.

Sound classes are a way to model distinctive features that define individual sounds. The difference between feature-bundle representations for sounds in sound change models is that features are flexibly defined on the fly, and modeled rather as “tags” of individual sounds, or a shortcut to reference the sounds that are tagged with a certain sound class name in an ordered manner. In our opinion, this comes quite close to the way feature bundles are used intuitively by linguists so far, since one can define one’s sound system in a convenient manner, and provide major distinctions that may play a role in sound laws, such as voicing distinctions of consonants:

voiced = b d g

voiceless = p t kAnother important aspect of sound classes is that they can be used as a shortcut for a group of sounds in sound laws, which often consist of an abstract set of independent sound changes, rather than an individual sound change that occurs in one context alone. As a result, one can refer to both individual sounds and to sound classes in the sound law descriptions of MISOL.

As a further note on the way in which sound classes are handled in MISOL, consider the following assignments:

voiced = b d g

voiceless = p t k

consonant = voiced voiceless m n ŋThis translates internally to the following major sound class representations:

{

"voiced": ["b", "d", "g"],

"voiceless": ["p", "t", "k"],

"consonant": ["b", "d", "g", "p", "t", "k", "m", "n", "ŋ"]

}Thus, if a sound class like voiced has been assigned to

a list of sounds, the label can be reused in order to assign the same

group of sounds to another sound class. Internally, all sound classes

are only represented as a group of terminal sounds, and only sound laws

can be reused in assignments if they have already be defined. As a

result, the following order of assignments would be problematic:

consonant = voiced voiceless m n ŋ

voiced = b d g

voiceless = p t kSince voiced and voiceless have not been

introduced yet with their target group of sounds, the interpreting code

of MISOL would treat them as individual sounds (which can be represented

by any string combination, provided it does not contain a space).

Invididual sounds, however cannot be assigned to another group of

sounds, since they are internally assigned to a group of one sound only,

so the program throws a warning here and ignores the corresponding

line.

Since MISOL does not care how you define your sounds, it offers the

possibility to work with groups of sounds as well as with individual

sounds when dealing with sound change. In order to make sure that we

distinguish groups from individual sounds, the recommendation is to use

a dot . between sounds in a sound sequence in order to

indicate that one is not dealing with individual phonemes. Thus, the

final or rhyme of a Chinese word like [kwaŋ]

could then be conveniently written as a.ŋ. MISOL, however,

will treat this sequence of grouped sounds as an individual sound class

(potentially a terminal one) and not assign it a specific semantics.

Since sound classes are ordered lists of sounds, nothing speaks against it if you assign the same sound multiple times to one and the same sound class. This may be important in cases where mergers are described in complex sound laws that deal with more than one input sound.

There are two symbols which are automatically defined as sounds,

which cannot be assigned to sound class groups: ^

represents the beginning of each word and $ the end.

# is reserved as a comment marker.

A sound law is an abstract formula that shows how one or more sounds in an ancestral language are converted to one or more sounds in a descendant language. It has the general formula:

source > target / contextThe number of source sounds and target sounds must be identical and the context is optional and can be omitted:

source > targetThe change marker > must be preceded and followed by

a space. So the following lines would be erroneous and lead to

errors.

source> target

source >target

source>targetThe same strict rules apply for the marker separating the context, the slash, which must be preceded and followed by at least one space. So again, the following lines will all yield errors and as a result, the line will be ignored.

source > target/ context _

source > target /context _

source > target/contextSource and target can be either a single sound, sound class, or list of sounds (indicated by square brackets), or a sequence of sounds.

If the source and the target are a list of sounds or a sound class, they must be of the same length. Otherwise, MISOL will throw an error. Thus, the following sound law is fine.

[a b] > [c d]Internally, it will be represented as two sound laws:

a > c

b > dHowever, the following is wrong.

[a b] > cThis means, if you want to define a merger, you must repeat the sound in the list of sounds as follows:

[a b] > [c c]If a sequence of sounds is provided (a sequence is defined by passing more than one sound, list of sounds, or sound class, without enclosing them in brackets), this will also be interpreted internally by invoking two or more separate sound laws, where preceding or following context is resolved automatically by MISOL.

This, the following code

a b > c d / x _ yis equivalent to writing

a > c / x _ b y

b > d / x a _ yA sequence of sounds can consist of individual sounds, sound classes, or lists of sounds. Thus, you could write a sound law as the following one:

[p t k] [a i u] > [p p p] [a a a]

This will turned all plosives to the sound

[p] and all vowels to

[a] if the former are followed by the latter.

If you want to combine sound classes to form a list of sounds, you can

put them into square brackets. Thus, you could define the following

sound classes:

unvoiced = p t k

voiced = b d gand then combine them to match unvoiced and voiced plosives in a single list in a sound law.

[unvoiced voiced] > [p p p p p p]In this sound law, all plosives are turned to a

[p]. However, if you write

unvoiced voiced > [p p p p p p]the sound classes are interpreted as consecutive sounds and the parsing won’t work. The following law, however, would work, since you define two lists that follow each other.

unvoiced voiced > [p p p] [p p p]Allowing to define consecutive sounds is thus a mere shortcut but it can come in handy in those cases where it seems difficult to define complex sound laws.

If you pass a sound class, a single sound, or a list of sounds does

not make a difference. Thus, if you have defined a sound class

ptk as shortcut for the sounds p,

t, and k, the following two statements are

equivalent:

ptk > ptk

[p t k] > [p t k]The same holds for sequences of sounds:

ptk ptk > ptk ptk

[p t k] [p t k] > [p t k] [p t k]Mixing is also possible.

ptk [p t k] > [p t k] ptkNote, however, that it is essential that the source and the target

always contain the same amount of sounds and the same

amount of positions. If you want to indicate the loss of a sound,

use the - as gap marker:

ptk ptk > ptk [- - -]Note in this example, that you cannot write a single gap symbol, but must assemble a group (or define a sound class with the group before), since we require to have one target sound for each source sound and vice versa. This means also, that you must repeat a sound when using sound class notations to formulate sound laws, where a merger happens.

[p t k] > [p p p]If you want to indicate that one sound turns into two sounds, which could happen in the case of epenthesis, you must provide the two sounds that replace the one sound in the original separated by a dot, as follows:

n > n.d / _ r [a e i o u]MISOL will internally replace the sound by the sequence

n.d in the respective context, but the final output will

provide the sound in merged form.

MISOL will in all cases represent sound laws individually, on the basis of one source sound corresponding to one target sound in one individual context.

The context typically has the form:

left_context _ right_contextHere, _ represents the source sound. Both left and right

context can be omitted.

left_context _

_ right_contextContext in left and right context is identically defined by a

segmental representation of the sound sequence proceeds to the left in

the left context and to the right in the right context. In this way,

theoretically even very long ranging contexts can be modeled. If one

wants to change an [s] followed by [p, t, k]

and a vowel to [ʃ], one can write:

s > ʃ / _ [p t k] vowelHere, the square brackets [ and ] are used

to indicate that the three sounds p, t, and

k represent a group that can alternatively occur in the

second position following the source sound. A full-fledged toy example

that would model that an s becomes voiced when followed by

a vowel and turns into a ʃ when followed by a consonant and

a vowel, one could define the following sound classes:

consonant = p t k b d g s z ʃ

ptk = p t k b d g

vowel = a e i o uThese could then be used in four sound laws:

s > ʃ / _ [p t k] vowel

s > z / _ vowel

p t k b d g > p t k b d g

vowel > vowelThese would turn a word like s t a b into

ʃ t a b but would turn s a b into

z a b. Defining groups of sounds with square brackets can

be done in a very flexible manner, and even sound classes can be placed

inside brackets in order to form new groups of sounds. One can, for

example, define two groups of sound classes for voiced and voiceless

sounds as follows:

ptk = p t k

bdg = b d gThese can then be used in combination in a sound law.

a > e / _ [ptk bdg]MISOL is based on the idea that a sound sequence is often best represented as a sequence consisting of multiple tiers (similar to multi-tiered annotation of texts in linguistic examples, such as interlinear-glossed text), that is, a matrix in which different aspects of the sequence are treated in segmental form. Tone, for example, can often be thought of as representing the whole syllable of a word in some tone languages, rather than only one of the sounds in the syllable, or the vocalic nucleus.

MISOL supports using multi-tiered sequences in two ways. First, one can define multi-tiered sequences in a very flexible fashion by just providing a matrix of symbols with as many tiers as one wants to use instead of using only one tier alown. A word in a tonal language, consisting of two syllables with two distinct tones, could thus be represented in the following form:

p a ŋ t a n

¹ ¹ ¹ ² ² ²In a similar way, one can represent stress in a word, e.g., by using the symbol 1 for stressed syllables and the symbol 0 for unstressed syllables.

f a t ə r

1 1 0 0 0Different tiers apart from the first segmental tier (called

segments in MISOL) can be addressed in the context

definitions in all positions by using the symbol @,

followed by the name of the tier, in front of the group of sounds

(marked by square brackets), preceding or following the sound in

question (or the sound itself). Thus, to indicate that an unstressed

[t] turns into a [d], one can write:

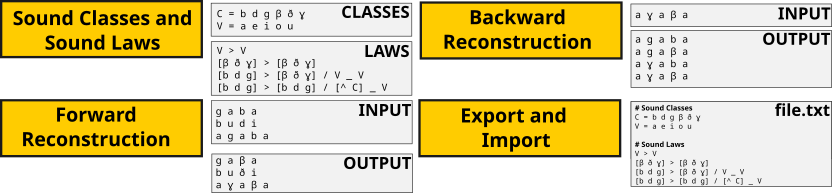

t > d / @stress[0]_When applying this sound law in forward reconstruction, one must provide both tiers (the segments tier and the stress tier) and pass the names of these tiers in the text field to the right of the field where one inserts the sound sequences to be modified, as shown in Figure 2.

The most common use-cases for sound laws with tiers is to define the specific tier value that holds for the segment that one intends to change (such as we have seen in the example). Other use cases, however, are also possible, when thinking of cases where a certain tier value holds for preceding or following sounds.

Instead of actively defining and passing new tiers

for individual segmental representations of sound sequences, one can

also make use of inbuilt functions in MISOL that compute tiers

automatically. An example is again the use of a specific tonal tier

(called tone), which is computed from the segmental

representation of tones using superscript letters at the end of each

syllable. Thus, passing a sound sequence such

p a ŋ ⁵ d a n ¹ will automatically yield a virtual

representation such as the following one internally in the MISOL

program:

p a ŋ ⁵ d a n ¹

⁵ ⁵ ⁵ ⁵ ¹ ¹ ¹ ¹As a result, tonal tiers can be used, as long as the tone values are

indicated by superscript numbers at the end of the syllable in each

sequence. In order to invoke these tonal tiers, one must indicate this

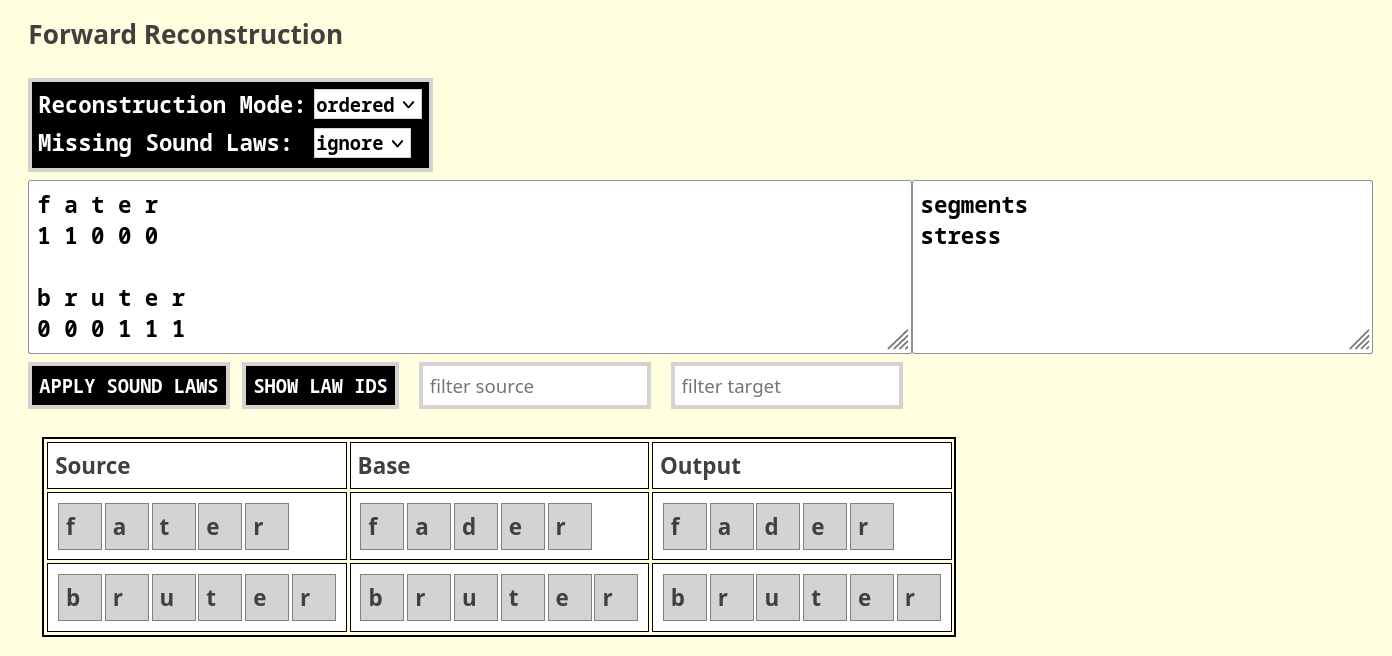

actively when using the forward reconstruction method (or the backward

reconstruction), by adding @tone as an additional tier, as

shown in Figure 3, assuming the following sound law:

d > t / @tone[¹]_

Apart from tonal tiers (called tone in MISOL), MISOL

currently offers three more tiers that can be automated, one tier that

checks for the nasality of whole words (returning 1 if a

words contains a nasal sound or a nasal vowel, and 0

otherwise), one tier for the initial sound in a word (returning the

initial sound for each letter in the word, called initial),

and one tier that handles the stress patterns of the word (requiring a

specific annotation that uses stress markers to mark syllable boundaries

in an explicit manner).

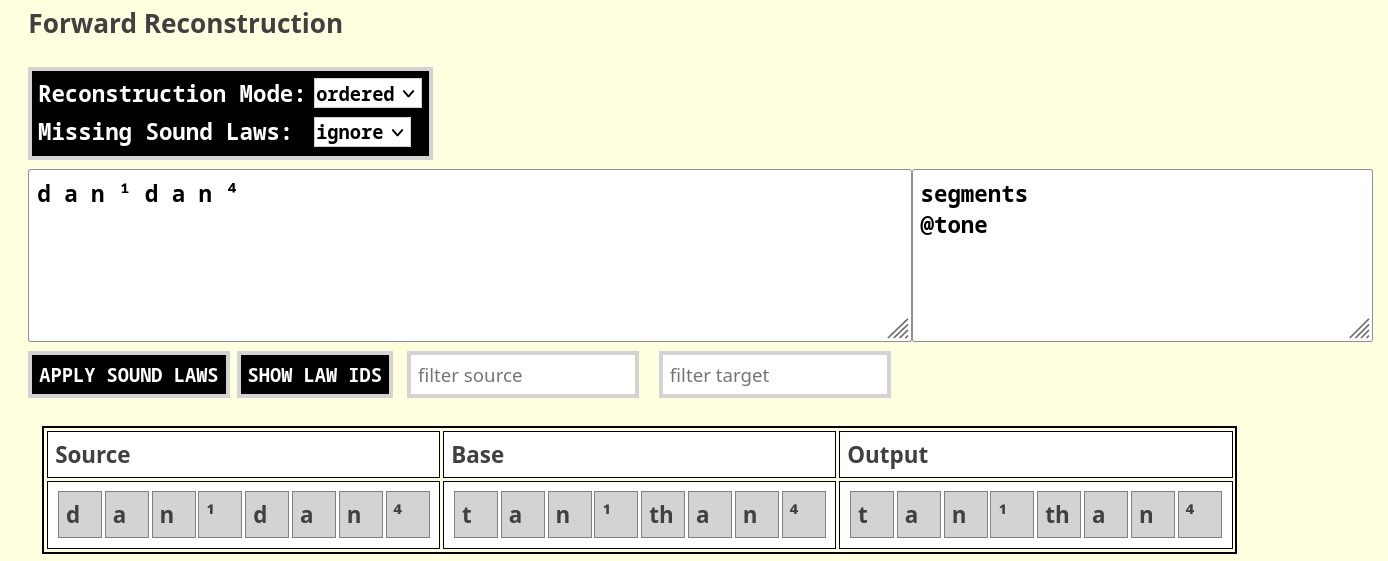

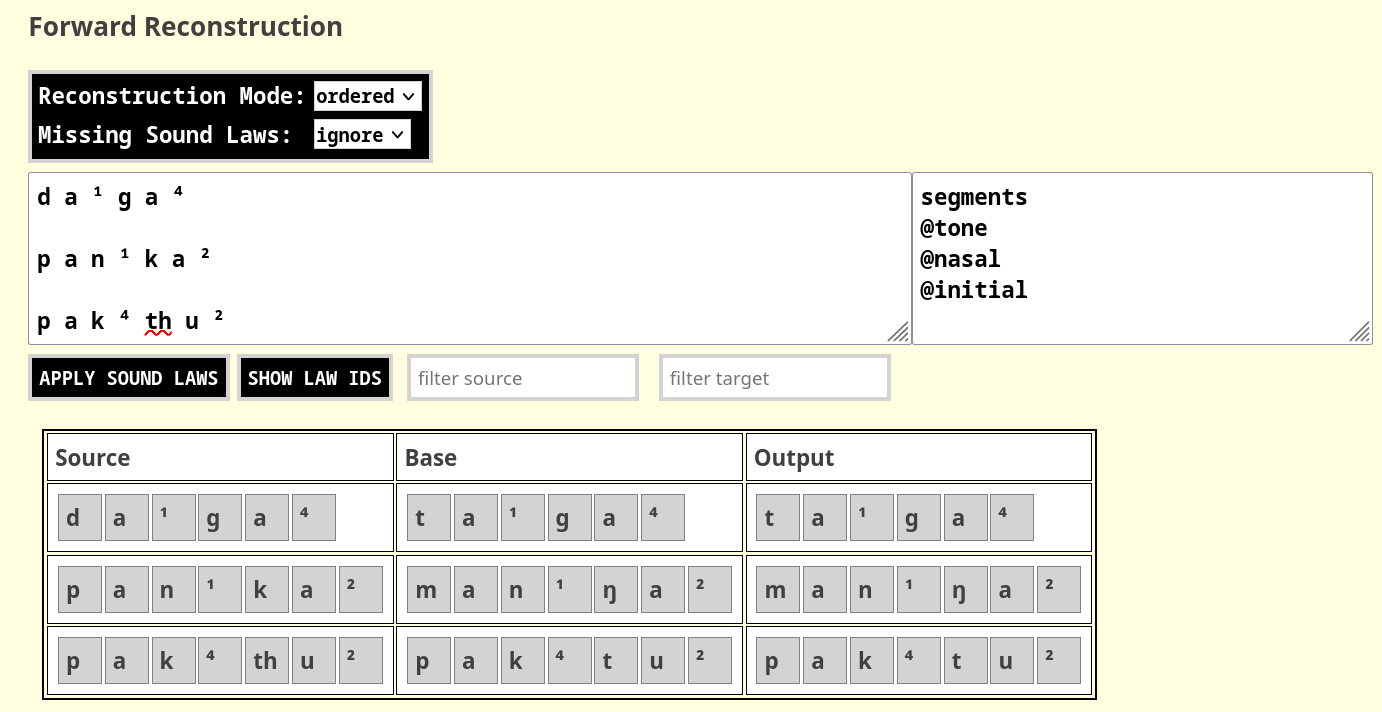

As an example, consider the following three sound laws that all use one of the three automated tiers.

d > t / @tone[¹]_

p > b / @initial[k]_

b > m / @nasal[1]_Figure 4 shows, how these can be applied to individual sequences, and where in the tool one needs to provide the information on the tiers that one intents to use.

In order to handle stress, stress must be marked in a specific

fashion that differs from the current handling in the International

Phonetic Alphabet. First, stress markers must be placed in front of

every syllable in a word, not only in front of stressed syllabes.

Second, stress markers receive their own slot, they should be separated

by a space from the rest of the sequence. Third, stress markers must

start with either the IPA stress marker ˈ or the quotation

mark ' (for convenience), or the secondary stress marker

ˌ, but stress markers can be expanded by adding arbitrary

symbols, allowing to mark different kinds of stress, such as “unstressed

by following a stressed syllable” (which would be needed for Verner’s

law. Thus, when defining the following sound law, one can handle

Verner’s law as well, by passing the sequence

ˈ f a ˌ t e r, in which we assume that the secondary stress

marker refers to unstressed syllables following a stressed syllable.

[p t k] > [f θ x] / @stress[ˌ]_The basic idea of MISOL is that sound laws often happen at the same time. For this reason, MISOL does not chain individual sound laws in order in order to let them derive a new sequence to which the next sound law is applied, but rather applies them all at once to the original context.

In most cases, these synchronous sound laws are sufficient and much easier to handle than consecutive sound laws. In some cases, however, it is clear that sound laws were active at different stages, called layer in MISOL. Thus, MISOl allows you to “layer” your sound laws by assigning them to different layers which are then executed in the order in which you provide them. As a simple example, consider how Latin generu- became gendre in French. While one could model this change in synchronous sound laws in many ways (for example also by just replacing e by a d when occurring between n and r), it is much easier and also closer to actual sound change to think of two different major changes that took place here. First, generu becomes genru, and then the epenthetic n emerges.

In order to model these sound laws in MISOL, you must assign individual sets of sound laws to a layer, by adding the layer name, placed in an equal sign, separated with a space, to the left and the right of the layer label.

= Layer 1 =

e > - / n _ r

= Layer 2 =

n > n.d / _ r [a e i o u]When applying these sound laws, MISOL will display all internal results, allowing you to track all intermediate forms that lead to the final form proposed by the tool, according to your sound laws.

An obvious limitation for which there exists no current solution in

MISOL is that context in MISOL cannot be selectively applied to the

source values. This means essentially that a process like assimilation

of [n] before voiced plosives [b

d g] must be represented in three distinct lines.

n > m / _ b

n > n / _ d

n > ŋ / _ ŋ

The reason why this is needed is that we cannot assign three different target values to three different contexts, as one might, however, expect (and I am sure there are enough examples in the literature, where people formulate sound laws in this way).

[n n n] > [m n ŋ] / _ [b d g]As of now, there is no other way but to spell all sound laws out, even if one feels that they belong together. It may, however, be possible that we find a solution for this problem in the future.

Forward reconstruction in MISOL is available in different flavors. What all approaches have in common is that MISOL first uses all available information on sound classes and sound laws in order to construct a virtual context window in which sound laws are supposed to take place. This window can be thought of as a multi-tiered sequence representation in which context is not handled on the horizontal axis, but precomputed for each segment in a sequence and represented in individual tiers, each corresponding to one specific context. For a sound law by which voiceless initials are voiced in intervocalic positions, for example, we would need two tiers apart from the base tier in order to represent context to the left of each segment and context to the right of each segment. The sound law could be represented as follows in MISOL (without using any sound classes), we add additional sound laws for completeness.

[p t k] > [b d g] / [a i u] _ [a i u]

[b d g] > [b d g]

[a i u] > [a i u]When dealing with a new sequence b a p a now, MISOl has

already inferred from the sound law, that we need two additional tiers,

and will now represent the new sequence accordingly, by providing for

each segment its right context and its left context.

| Tier | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segments | b | a | p | a |

Segments_Left |

^ | b | a | p |

Segments_Right |

a | p | a | $ |

From the sound laws shown above, MISOL will construct vectors that represent individual contexts. These sound laws are based on the Cartesian product of the different sounds that can appear in the left and the right context and thus capture all eventualities, as shown in the table below, that shows the individual vectors for the three sound laws (in abbreviated form).

| ID | Law | Segments | Segments_Left |

Segments_Right |

Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | p | a i u | a i u | b |

| 2 | 1 | t | a i u | a i u | d |

| 3 | 1 | k | a i u | a i u | g |

| 4 | 2 | b | Ø | Ø | b |

| 5 | 2 | d | Ø | Ø | d |

| 6 | 2 | g | Ø | Ø | g |

| 7 | 3 | a | Ø | Ø | a |

| 8 | 3 | i | Ø | Ø | i |

| 9 | 3 | u | Ø | Ø | u |

When iterating over each position in the multi-tiered sequence, MISOL

will try to find which of the laws (as shown in the table) provides a

vector that matches the current vector in the sequence. The symbol

Ø is a wildcard marker and matches with every sound. For

our example, we can contrast the actual tiers with the precomputed

individual sound laws as shown below.

| Tier | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segments | b | a | p | a |

Segments_Left (Source / Context) |

^ / Ø | b / Ø | a / a i u | p / Ø |

Segments_Right (Source / context) |

a / Ø | p / Ø | a / a i u | $ / Ø |

| Sound Law / ID | 2 / 4 | 3 / 7 | 1 / 1 | 3 / 7 |

| Target | b | a | b | a |

This is the major procedure used by MISOL in order to turn one source sequence into one target sequence. The method (1) precomputes the context for the sequence, which allows it to (2) iterate over each position regardless of the order, searching for matching patterns and their corresponding output.

The procedure as outlined here is what is called the “strict” mode in MISOL when using forward reconstruction. It is called “strict” with respect to the mode of reconstruction, since it does not tolerate that different sound laws match the same context and yield different output (MISOL will explicitly mark these cases). Users can choose between the strict mode and the “ordered” mode, in which the matching process is modified in such a way that in the case of competing sound laws, the law that was defined first, wins. This makes coding sound laws much more convenient, since one can first define a very strict law and later define a general law that would hold for all other cases not touched by this first law.

s > ʃ / _ [p t k]

s > sWhen passing a sequence s p a s a to this sound law, it

would yield the output s|ʃ p a s a in strict mode, and

ʃ p a s a in ordered mode, using the pipe to indicate

competing sounds (see List et al. 2023

for this notation).

Scholars typically omit the “boring” sound laws from their descriptions, specifically those cases of sound change, where no sound change happens. Thus, we rarely find a sound law as the following in the literature.

t > tMISOL tolerates the omission of not providing sound laws in those cases where sounds don’t change. The Forward Reconstruction tab offers users to select whether missing sound laws should be marked or ignored. If they are ignored, the original sound is used unchanged. If they are marked, the sound will be preceded by an exclamation mark and marked in red.

At the moment, you can only pass explicit tiers (such as accent) once. Since their main purpose is to be able to explain the initial change, they cannot be used in consecutive sound law processes, since this would require us to add a routine by which tiers from a source word turn into tiers from a target word. +++Using computed tiers is not yet implemented by will be available at some point.+++